Striking Biases

Seeing the expected

OSSOS VI. Striking biases in the detection of large semimajor axis Trans-Neptunian Objects. (Shankman et al., 2017)

Available on ArXiv, to appear in AJ

Science

An important point in this discussion is that what’s happening here is the scientific method, keep in mind how science is meant to work:

- Data gives suggestions and people provide interpretation which leads to an hypothesis.

- The hypothesis is then tested against independent data.

This is what science is about.

Our results don’t say there can’t be, or isn’t, another large mass planet in our solar system, those data just say their doesn’t need to be one.

Frequently Asked Questions

- The key points:

- The clustering of distant TNO orbits is used to argue for the existence of a very large additional planet in the outer Solar System.

- OSSOS is a large mapping survey of the outer Solar System, which began in 2013, before additional planets were argued for.

- Statistical testing of the distribution of orbit shapes and orientations is made possible by the precise calibration of OSSOS.

- Eight of the minor planets that OSSOS has found are on large orbits of the sort used to argue for a planet: they have closest approaches to the Sun that are beyond Neptune’s orbit, and mean distances that are greater than 150 astronomical units.

- We have simulated the OSSOS sensitivity to a wide range of orbit shapes and tilts.

- Using our new independent sample, OSSOS finds that the orbit distribution in the OSSOS sample is fully consistent with being drawn from a uniform sample and does not require the orbital clustering in the outer Solar System that others have claimed.

- We show how apparent clustering of orbits can be a natural outcome of the effects of observing the sky. Certain orientations of distant TNO orbits become easier or harder to discover, from the combination of weather through the seasons and which part of the sky is observed. These effects may have led to the two apparent “clusters” among the discovered distant TNOs.

-

What is a trans-Neptunian object (TNO)? A minor planet (known TNOs range from 50-500 km across) that goes around the Sun a long way out, beyond the orbit of the icy giant planet Neptune. They are small worlds left over from the early formation of the Solar System. Their orbits today tell us about how in the past the giant planets of the Solar System have changed where they orbit.

-

Why might there be a distant planet? Since 2002, a small number of TNOs have been found on orbits that are particularly large, and at closest approach are still outside Neptune’s orbit. There are simulations by other scientists that suggest if a planet exists, it would be able to shepherd their orbits together in space, forming two clusters, while other simulations do not show this effect. As we find more distant TNOs with large orbits, the orientation of their orbits in space tests the idea that there is a clustering in the orbit distribution.

-

Do the known large-orbit TNOs show clustering? The claim that clustering is present in the known set of large-orbit TNOs was based on combining the rare discoveries of distant TNOs from many different surveys. However, the sensitivity of those surveys is incompletely known. Also, the spread of distant TNO orbits that an extra planet would make was hard to distinguish from the Solar System as we know it, given the current surveys.

-

What is OSSOS? A survey to hunt for trans-Neptunian objects and carefully measure the path they take around the Sun. OSSOS – the Outer Solar System Origins Survey – used the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope to look at eight patches of sky throughout each year over 2013-2017. More than 800 TNOs were discovered by OSSOS, doubling the number of known TNOs with accurate orbits; most of them orbit relatively near Neptune. OSSOS was not designed to hunt for extra planets, nor for the large-orbit TNOs. However,we have found eight large-orbit TNOs among our 800+ discoveries. These eight are useful in testing for the existence of a planet.

- Why is this set of eight discoveries special?

The eight OSSOS discoveries are all from a single, exquisitely calibrated survey, and there are roughly as many of them as in the previous combined set. They form an independent test of the idea that a massive planet at extreme distance from the Sun is shaping the outer solar system.

- The eight OSSOS discoveries have orbits oriented across a wide range of angles.

- The observed orbits are statistically consistent with random.

- The OSSOS detections do not all follow the pattern seen in the previous sample.

- One of them sits at right angles to the proposed two clusters.

- The orbits are not tightly clustered.

-

How did you test for any clustering effect from a distant planet? We simulated the orbits of a uniform spread of tens of thousands of distant TNOs. We tested which ones would be visible to our survey. The simulation showed that there are areas of the sky, like the dense star fields of the Galaxy, where certain orientations of TNO orbits become very hard to discover. We find that the clustering effect that has been attributed to a planet could easily result from a combination of seasonal weather (the TNOs are all discovered in limited ground based observing projects) and where in the sky it is easier to discover distant TNOs.

- So… is there a planet? OSSOS can not prove, or rule out, the existence of the hypothesized “Planet 9” (a planet more than 10 times the mass of Earth and on an orbit that extends beyond 500 astronomical units). The idea of a dwarf planet, maybe as big as Mars, is still entirely possible. The OSSOS discoveries and observational simulations (using our extremely well-calibrated survey) substantially weaken the evidence that has been used to justify the need for an additional very massive planet in our solar system.

For additional information please contact:

North America

- Cory Shankman : cshankm@uvic.ca

- Samantha Lawler : Samantha.Lawler@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

- JJ Kavelaars : jj.kavelaars@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

- Brett Gladman : gladman@astro.ubc.ca

Europe

- Michele Bannister : M.Bannister@qub.ac.uk

ASIA

- Ying-Tung Chen : ytchen@asiaa.sinica.edu.tw

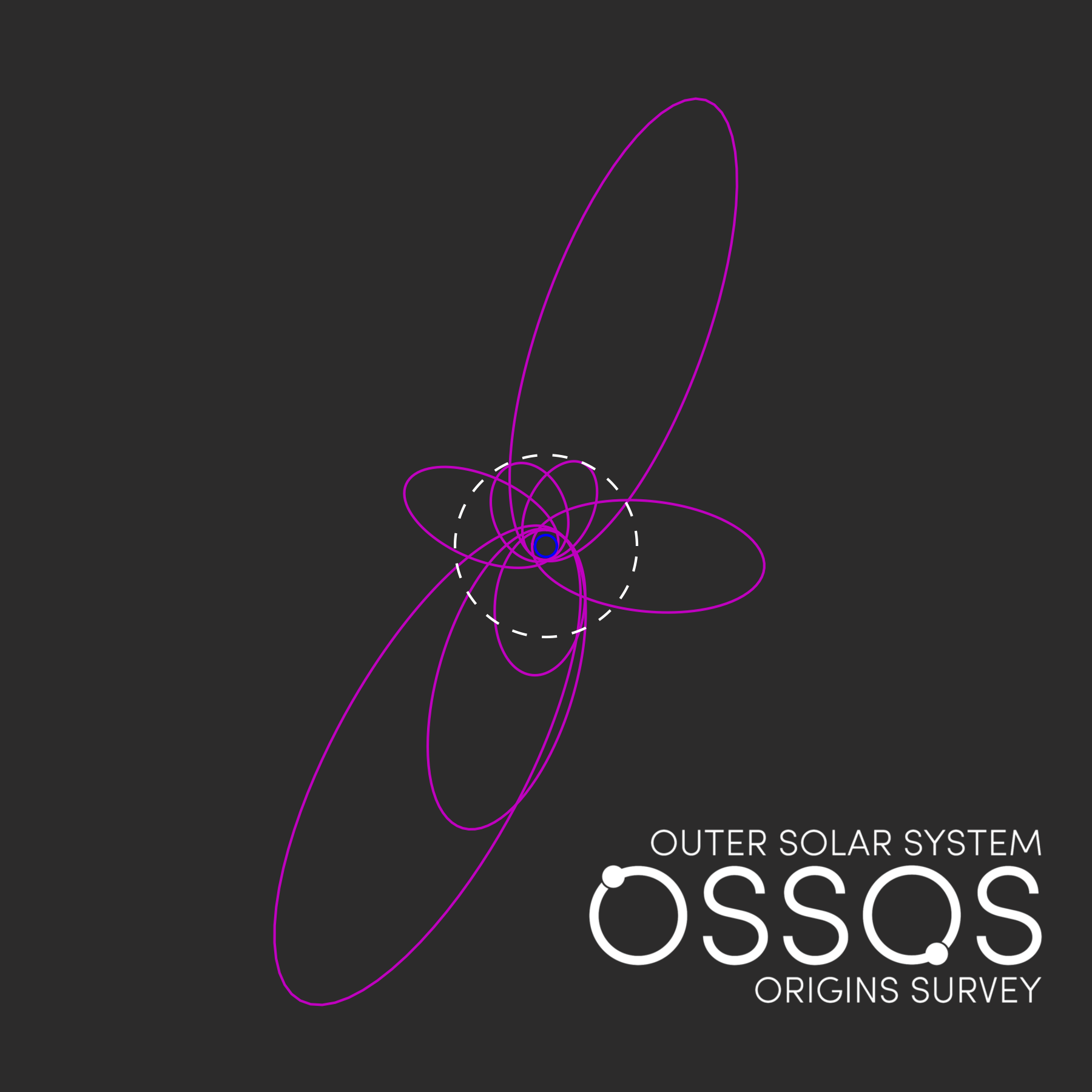

Labelled versions of the plot above are available, which identify all the objects: labelled with Minor Planet Center designations or with the OSSOS designations.